My latest trip to Okinawa happened, by chance, to align with the exhibition “Heavy Pop” at the Okinawa Prefectural Art Museum – the first large-scale solo show of Teruya Yuken’s work to be held in Okinawa. I have been fortunate to see Teruya’s work a number of times now, in smaller galleries in Okinawa, at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo, and elsewhere; seeing so many works all together here it was really fantastic to start to get a better sense of the themes that run through so much of his work.

The exhibit opens, at first, with groups of balloons and pictures of balloons, and I think there is really something wonderful about the interplay between works being colorful, visually appealing, visually interesting, and at the same time deep with meaning. So much of what we see in this exhibit is just plainly colorful, fun – it brightens our day. Or it is visually interesting, capturing our attention at first simply by its creativity, as Teruya displays entire cars upside-down in the gallery, stacks of newspapers with little cutouts rising up out of them in the shape of seedlings or sprouts, gorgeous bingata robes, or a sprawl of cardboard pizza boxes. But then we look closer, take another moment to think a bit more about the meaning or ideas suggested or addressed in these works, what histories or issues or ideas they might be addressing, referencing, or conveying, and there are always these deeper, intriguing, often emotionally powerful or thought-provoking, layers.

Entering the gallery, we see a line on the ground leading straight down the corridor, with a small number of bright red balloons floating freely to either side. Do we walk the straight line, along the path set out for us? Or do we deviate, and walk off the path?

A large bundle of balloons is tied together and tied to a rusted piece of metal shrapnel from the Battle of Okinawa. Do we see the balloons as lifting up this piece of WWII shrapnel from the ground, or the shrapnel as weighing down the balloons? Certainly, the upward pull of the balloons is, in total, here, stronger. They are not being weighed down all the way to the ground; to the contrary, without the ceiling, they would float away. But the weight of the shrapnel is still very tangible as we view this bunch of balloons, and as we (with permission) touch the shrapnel and feel the pull upwards and downwards ourselves. The people of Okinawa continue to build a better, brighter, future, with hope that lifts people up, but the weight of the legacy of the war is still there.

We tend to think of Aug 15, 1945, as the one and only date of Surrender, as if it all happened instantly. It took some time for the actual, logistical, on-the-ground, surrendering of each individual set of troops to take place. Sept 7, 1945 marks the final, official, surrender of Japanese generals in the Ryukyu Islands to their American counterparts.

Yuken puts small bits of personal items found along with the bodies of those who died in the war up for sale in the gallery. How can we put a price on – and buy and sell and trade in – items so immediately associated with war and with death, the personal items of people who died? How can we think of the preciousness of life, and the emotional significance of war memory, in terms of monetary amounts? And how can we be complicit in allowing such items to be dispersed into private hands, including overseas, in the hands of collectors all around the world? But. But, on the other hand, local Okinawan museums, peace museums across Japan, have so many such items. They genuinely have no need for more, and it costs space, human resources, etc. to keep such collections. So, conversely, as the curator Oshiro Sayuri explained to me, perhaps it actually is better that people buy these, and use them in whatever way they do – for education, for telling the stories of the war. And while I’m not sure where the money goes to, from people who do buy these things, regardless of whether it goes to the Museum, or Yuken, or to non-profit orgs dealing with recovering remains (still!) from war sites, either way it does go to support Okinawan arts, culture, and/or non-profits doing meaningful work.

Teruya is a rather prolific artist, producing works in many different media, and within each series also, creating not just one piece but many variations on an idea. His bingata robes, designed by Teruya and hand-dyed by a master of this traditional Okinawan textile art, are perhaps one of the types of works for which he is most well-known. But he did not make just one or two or three of these and move on; there were many of them in this exhibit.

At first glance, these resemble fully traditional-style bingata robes, ornately decorated with designs of birds and flowers and so forth. But look closer, and you quickly realize that Teruya has hidden in the designs a mix of historical and contemporary elements – particularly elements related to the ongoing struggle with the extensive US military presence in the islands. We see paratroopers, fighter planes, dugongs (a manatee-like sea creature severely endangered by the current US military base expansion project at Henoko Bay), barbed wire, and English text taken from Occupation-era or other military contexts. So much of contemporary Okinawan art is read as being a clear and direct critique of war, of militarism, of the dangers to lives and land. But in these pieces, I also read a critique that’s closely related, but maybe different in nuance: that is, in these bingata robes we see an infiltration, an altering, of what is Okinawan iconography, Okinawan culture. Is this Americanized, military-influenced, culture, “Okinawan culture”? Is this what Okinawa is, what Okinawa means, today? In one of the newer bingata pieces, we see the Main Hall of Sui gusuku (Shuri castle), the former royal palace of the Ryukyu Kingdom, featured prominently. The palace was destroyed in World War II because of a Japanese military headquarters hidden beneath it; this Main Hall, and a number of surrounding central buildings, were restored and opened to the public in 1992, and quickly took on great meaning for many Okinawans. These central buildings were then tragically lost again, in an accidental fire in 2019, and are now being restored once again. So, we have this symbol of the kingdom’s sovereignty and of Okinawa’s vibrant, rich, distinctive traditional culture, contrasted with all these symbols of the US military presence which so colors life in Okinawa today.

It’s About Me, It’s About You. It’s about solidarity between all minority or indigenous peoples, all people of the world. Yuken takes newspapers talking about large-scale marches against US militarism, against the stationing of Osprey VTOL aircraft in Okinawa, which are noisy and which have crashed so many times, and in my interpretation he tries to draw attention to these issues, posting in multiple languages that we are all linked together. Some issues in the world attract a disproportionate amount of attention, but I believe Teruya is calling upon us to turn our attention, yes, to Israel and Palestine, but also to Okinawa and Myanmar, and though not featured explicitly here, I would add, to Hawaii and Xinjiang, to Lebanon and Iran, to Ainu Moshir and Puerto Rico, and so many other places where people are suffering, and to recognize our shared humanity. To see one another, and our struggles, and to cultivate compassion, sympathy, support for one another, across the world.

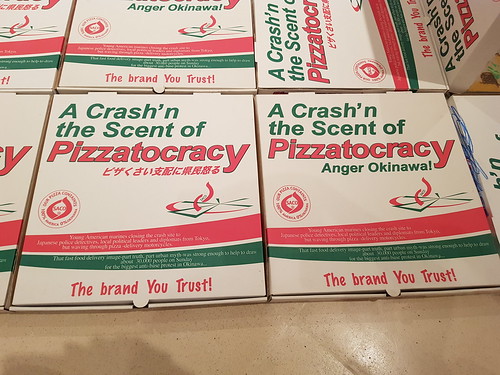

In 2004, a US military helicopter crashed on the grounds of Okinawa International University. US military immediately took over the site – private land belonging to a Japanese/Okinawan institution, not US land! – and blocked nearly anyone, from professors and students to local Japanese/Okinawan law enforcement, first responders, and journalists, from entering the site. Only the pizza delivery people were allowed in.

Teruya created these wonderful pizza boxes, covered in phrases satirizing and commenting on the event, and reprinting a segment from NYTimes reporting, and created a community event in which he asked local people – children, grandparents, and others in-between – to draw images inside the boxes.

A pair of flipped cars, accompanied by planning drawings and video of the flipping event, remind me of the annual Naha Tug-of-War or other centuries-old local village festival traditions, even as they also recall the Koza Uprising of 1970, the only major violent protest I’m aware of in the entire 27-year period of the Occupation (1945-1972). Americans’ cars were flipped and torched, as Okinawans expressed their frustrations with life under Occupation in a spontaneous, unplanned, outburst of collective anger.

This is only a sampling of what was a rather extensive exhibit. But I think I’ll leave it at that for now. Always wonderful to see Teruya’s works – his creative, clever, and so beautifully executed works that are at once both visually appealing / intriguing, and rich in political meaning.