As I gradually made my way, one character at a time, through the primary source document I’m reading right now, I came across the name/title Matsudaira Izu no kami1, and I had a thought. I don’t know if anyone has written on this, if there is any scholarship on it, or if there’s any real supporting evidence, but, it’s just a thought.

The document refers to Matsudaira Izu no kami without any indication of a given name. Now, certainly, there are all sorts of potential reasons for this, in terms of etiquette and politeness, respecting and honoring the title or the position instead of referring to the individual, and/or reserving the use of the personal name for personal relationships. But, the thought occurred to me, does it matter to the person writing the letter who this Matsudaira Izu-no-kami is? Does he care whether this Matsudaira Izu-no-kami is the father, or the son, whether he is Matsudaira Nobuyori or Matsudaira Kazunobu or Matsudaira Tadakazu?2 Whether he is this sort of person, or that sort of person, in terms of physical appearance or personality? Or does the author of the document only think of Matsudaira Izu-no-kami as a position, as a person embodying that hierarchical and administrative position, as a member of the Matsudaira clan more or less interchangeable for any other member of the clan who might alternatively be occupying that title, or position, of Izu-no-kami?

What if, when you inherited a name or title, you weren’t just taking on the name or title while retaining your own individual identity? What if the common cultural understanding at the time was, rather, that you’re taking on that identity as well, subsuming, replacing, or erasing your own individual identity, and becoming a continuation, or embodiment, of that identity?

It was quite common in the Edo period, particularly within certain trades, for a son or successor to have the exact same name as his father, or predecessor. Look through Andreas Marks’ book on Edo period publishers, and you’ll find that a great many of them seem to have been active for spans of nearly a hundred years, or in some cases even longer. Moriya Jihei, whose publications included works by ukiyo-e greats Hokusai, Utamaro, and Kunisada, was active from roughly 1797 to 1886. Clearly, there was more than one individual operating under this name; it is exceedingly unlikely that a single person, by the name of Moriya Jihei, could have lived that long. Now, individual identity seems to us today pretty natural, and obvious – on at least some level, surely, people of any time and any culture would have had to recognize that one person (e.g. the original Moriya Jihei) has grown old and died, and that a different person, younger, with a different face and a different personality, has taken his place. I don’t think I would ever want to go so far as to suggest that there was no concept whatsoever of individuality in the Edo period. But, is it not possible that there was, at least to some extent, some idea of this young man as being the [new] Moriya Jihei, and not an entirely different person who’s taken on the name alone?

Perhaps what I’m getting at might be seen best in the arts. People expect a certain style from Hiroshige, or from Toyokuni. And they get (pretty much) the same style, the same themes and subjects, from the figures we today call Hiroshige II or Toyokuni III. In our individual-oriented conception today, we might say all kinds of things about Hiroshige II or Toyokuni III being separate individuals, with individual personalities and desires, taking on the name of their teacher because of custom/tradition, and/or applying that name in order to continue to sell an established, popular “brand.” But what if – and I’m not saying it was the case, but only that it would be an interesting phenomenon if it were – what if people at the time saw these artists not as new, different, individuals who had taken on a name, not as new, different artists with their own unique interests and styles, but as truly continuations of the same identity?

To make it even sharper, take the case of Kabuki. The history/historiography of kabuki of course recognizes the birth and death dates, life events, and unique personalities, skills, and talents of individual actors such as Ichikawa Danjûrô VII or Onoe Kikugorô III. But, kabuki tradition also holds that there are certain roles and techniques at which Danjûrô or Kikugorô excel, and in each generation, the actor bearing that name was expected to reflect those talents. In the West, we might say that so-and-so Jr. was really good at X, Y, and Z, while his father so-and-so Sr. was a completely different person. Charlie Sheen is not Martin Sheen, Beau Bridges is not Lloyd Bridges, Kiefer Sutherland is not Donald Sutherland, and we wouldn’t expect them to be, even if any of them did have the same name (e.g. Martin Sheen Jr.). Kabuki actors, on the other hand, are expected to not simply emulate or imitate the performance style of their predecessors, but, in a way, to be their predecessors. Danjûrô I (d. 1704) excelled at, among other techniques and distinctive moves, crossing his eyes and popping them out, and ever since then, each Danjûrô has been expected to do the same. To be unable to do so would mean not being Danjûrô — this is something that Danjûrô is famed for, and you’re Danjûrô, so you should be able to do it. Even if our more individual-oriented approach tells us that popping your eyes out, or crossing your eyes, like wiggling your ears or curling your tongue, is simply something that some people can and some people cannot do. Similarly, Onoe Kikugorô is famed for his ability to play both female roles and male roles, and especially for his skill, or talent, at playing both at once – in the play Benten Kozô, he plays a man disguised as a woman, who then strips his/her disguise and reveals himself within a scene. In the Western tradition, we might identify this as the special talent of one particular individual, saying, Onoe Kikugorô V was really especially good at this, and Kikugorô VI wasn’t, but Kikugorô VI was really good at such-and-such other thing… I don’t think this happens quite as much in kabuki. Kikugorô VI is Kikugorô; he’s the Kikugorô, the only Kikugorô (of this current generation, of this contemporary moment), and he is expected to perform, and embody, all that Kikugorô is expected to be.

Again, I don’t know that people in the Edo period generally, or even to whatever extent, or in whatever ways, did or did not think about identity and individuality in this way; I don’t have extensive evidence or scholarship that I’m drawing upon right now. I’m not saying it was, but only what if it were, and isn’t that an interesting thought. How did people of the Edo period view individual identity, and the relationship between individual identity and names?

—

1) I’m surprised to not find any good pages to link to online to explain the term “kami” (守) but, essentially, being the “kami” of a province, e.g. Izu no kami 伊豆守, or Satsuma no kami 薩摩守, was an honorary court title. It had no direct connection to the province a given lord was from, nor the province where he held power, and was purely a symbolic/honorary/ceremonial title. Nevertheless, this was a very prominent way of identifying people.

2) I’m making these names up, and not referring to anyone in particular; which is, essentially, the point. The name, and the individual identity, doesn’t seem to matter to the writer.

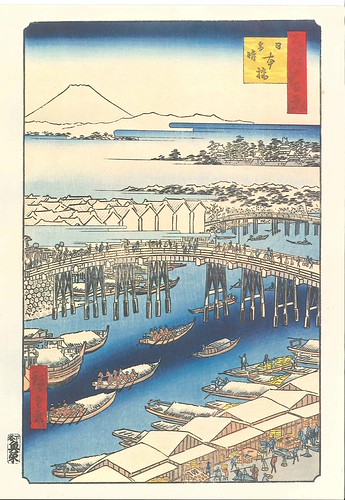

It is interesting to compare the form of Fujifs peak in the pictures here. Shigenaga carries on the medieval tradition of showing the medieval teikei of three symmetrical peaks. But Hokusai and Hiroshige, however, there is no real teikei: each artist shows the peak in an individual way, no longer perfectly symmetrical. Yet it is in no way a jikkei: the slope is far steeper than in reality, and it is immensely larger than life. The actual Fuji seen from Suruga would have appeared even lower than the rooves of the buildings.